Greenhouse gas emissions from the legal marijuana industry have climbed so quickly in recent years that they now equal that of about 10 million cars, according to a newly published study into the energy and emissions of cannabis production. A switch from indoor to outdoor grows, however, could lessen that environmental impact by lowering emissions as much as 76 percent.

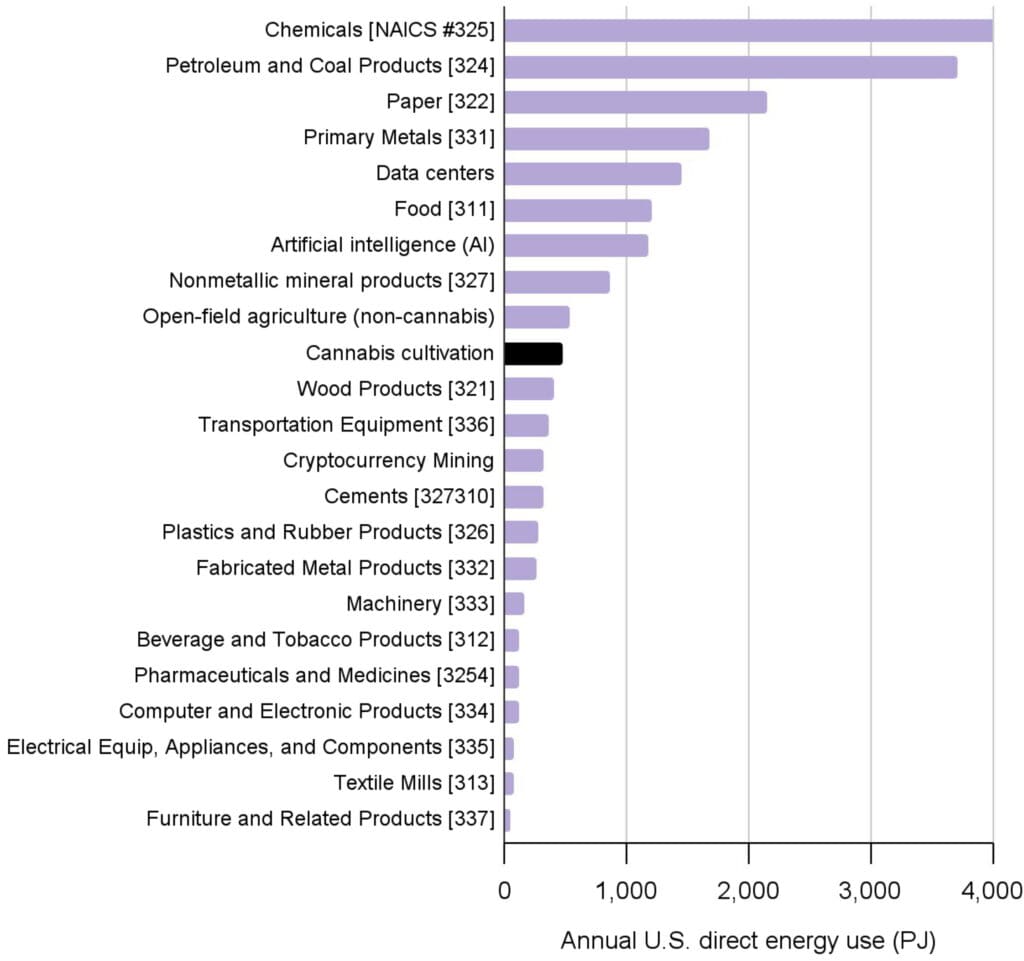

That’s according to Northern California-based researcher Evan Mills, who has spent years building a model of the legal cannabis industry’s energy inputs and emissions outputs. All told, his new paper in the journal One Earth concludes that energy use by the sector is “on par with that of all other crop production,” and that the marijuana industry represents 1 percent of “total national emissions from all sectors of the economy.”

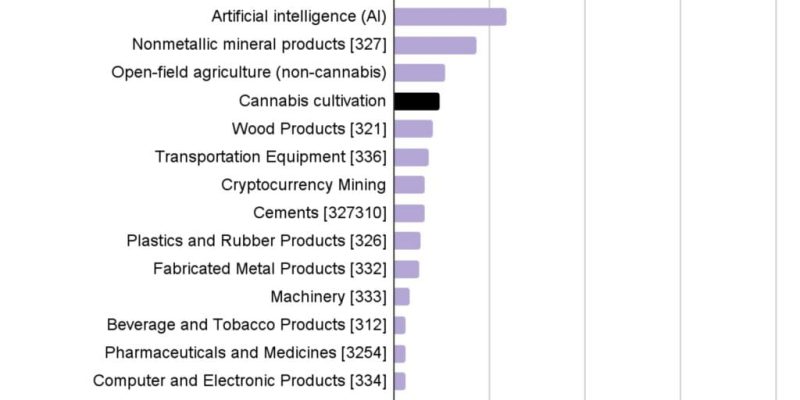

Compared to other industries, the study continues, “direct, on-site use of fuels and electricity by the cannabis industry is 4 times that of domestic use by the US pharmaceutical industry and beverage and tobacco manufacturing.”

“Energy use is a third of what is used by data centers nationally,” it adds, “and 1.5 times that of cryptocurrency mining.”

Mills’s lifecycle analysis includes not just cultivation itself, but also transportation, retail and waste disposal.

“Cannabis has become the most energy- and carbon-intensive crop,” the author wrote, “as cultivation has shifted from open fields to indoors, covering an area of ∼5 million square meters (∼270 average Walmart stores) in the US.”

That physical footprint, he noted, is “greater than that dedicated to artificially lit food production and floriculture across the country.”

Evan Mills / One Earth

But not all cannabis production is equally responsible for energy use and emissions. Mills’s report asserts that about 90 percent of marijuana-related emissions come from indoor grows, which are far more energy intensive than outdoor cultivation.

“Indoor cultivation can also yield worse outcomes for indoor and outdoor air quality, power grids, waste production, water use, energy costs, worker safety, and environmental justice.”

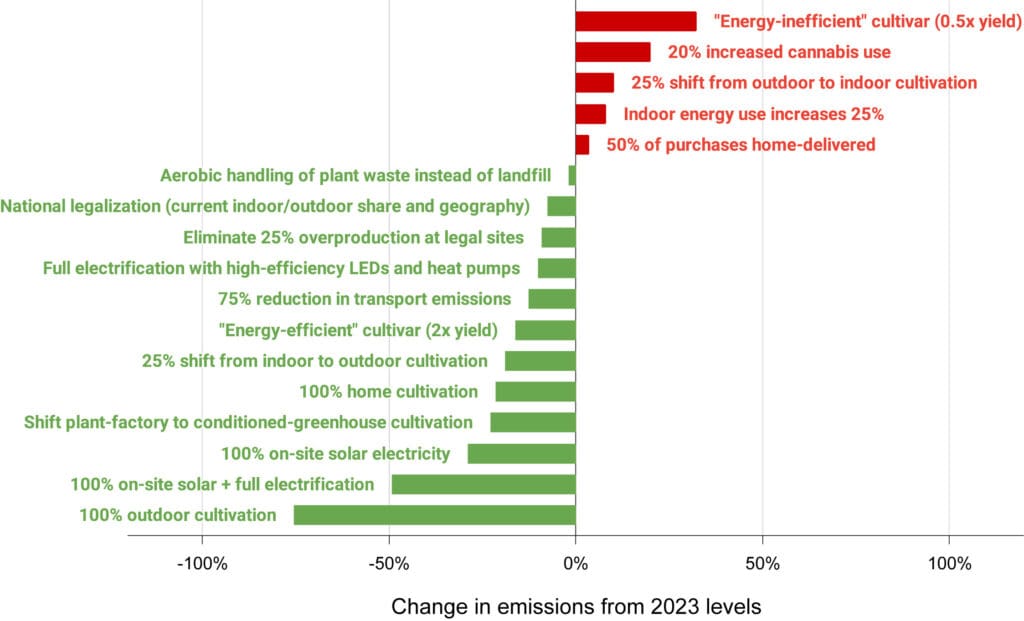

As far as reforms go, the new paper says federal legalization of marijuana “would achieve only modest reductions” in energy and emissions—about 8 percent overall—though it notes a national-level reform “could enable more potent policies.”

The most promising is a pivot away from indoor grows and toward outdoor cultivation.

“Emissions have risen substantially despite widespread state-level legalization efforts, which suggests that relying on market forces alone is not a viable climate strategy for this industry,” the report says. “More targeted policy initiatives are needed to manage emissions, and the greatest potential lies in guiding the industry toward a much larger share of open-field cultivation.”

Additional policy shifts that could reduce emissions include increased home growing of cannabis, wider use of greenhouses by cultivators, use of more energy efficient varieties of the plant, implementation of on-site solar and other updates.

But there’s also a risk of increasing emissions in the new legal cannabis era. For example, if more marijuana is grown indoors, or if more products are delivered directly to consumers’ doors, emissions would rise under the model.

If half of all sales were done through deliveries, that would increase emissions by 4 percent, the study says. Meanwhile if a quarter of all outdoor-grown cannabis were shifted indoors, that would lead to a 10 percent emissions increase.

“Key upward pressures include rising demand for cannabis, changes in industry structure, reversion of legal producers to the illicit market (where electricity sources can be dirtier and less efficient) in response to what are perceived as overzealous regulations, and a trend toward derivative products that embody added processing energy,” the report says.

Evan Mills / One Earth

Mills said that while consumers have access to information about energy consumption around other types of products, that information typically isn’t available for cannabis.

“Consumers don’t know any of this,” he told The Washington Post. “They know that a car is labeled with how many miles per gallon it gets, or a refrigerator has an Energy Star label, but there’s zero consumer information about cannabis.”

One factor the new analysis doesn’t account for is interstate commerce, which lawmakers could approve as part of federal legalization or separately. That would allow regions better suited to outdoor cannabis cultivation to grow more marijuana outdoors and sell it elsewhere.

Mills’s model of federal legalization doesn’t dig into that dynamic. “The ‘full legalization’ case,” his paper says, “does not model the possible effects of relaxing restrictions on interstate commerce or other policies that could be deployed in a legal market.”

Nevertheless, it continues, “In the event that interstate transport bans were lifted, related questions would be whether states with climates that do not favor open-field cultivation…would opt instead to import from states where it is more feasible (and where indoor cultivation is also less energy intensive).”

Currently, the paper notes, cultivation is trending the wrong direction. “Large-scale legal indoor cultivation is increasingly concentrated in environmentally overburdened urban areas,” it says, “as seen in Oakland and Denver, each of which host about 200 sanctioned plant factory operations.”

The new study comes on the heels of separate research last year finding that “outdoor cannabis agriculture can be 50 times less carbon-emitting than indoor production.”

Authors of that report, published in the journal Agricultural Science and Technology, noted that while a handful of studies have examined indoor marijuana production, “very little is known about the impact of outdoor cannabis agriculture.”

“Dissemination of this knowledge is of utmost importance for producers, consumers, and government officials in nations that have either legalized or will legalize cannabis production,” they wrote.

Though the environmental impacts of cannabis production are often overlooked by policymakers, industry and consumers alike, some bodies have stepped up efforts to lessen the footprint of cultivation.

In Colorado in 2023, for example, officials launched a program to fund the cannabis industry’s energy efficiency, pointing to a 2018 report from the state’s energy office finding that cannabis cultivation comprised 2 percent of the state’s total energy use. Electricity was pricey for growers too, the report found, eating up roughly a third of cultivators’ operating budgets.

In 2020, Colorado launched a more experimental program aimed at using cannabis cultivation to capture carbon from another regulated industry: alcohol. The state Carbon Dioxide Reuse Program Pilot Project involved capturing carbon dioxide emitted during beer brewing and using the gas to stimulate marijuana growth.

A 2023 report from the International Coalition on Drug Policy Reform and Environmental Justice, meanwhile, drew attention to the negative impacts of unregulated drug production in areas like the Amazon Rainforest and the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Attempts to protect those critical ecosystems, the report warned, “will fail as long as those committed to environmental protection neglect to recognize, and grapple with, the elephant in the room”—namely “the global system of criminalized drug prohibition, popularly known as the ‘war on drugs.’”

In 2022, meanwhile, a pair of U.S. congressmen who oppose legalization pushed the Biden administration to study the environmental impacts of marijuana cultivation, writing that they had “reservations regarding marijuana cultivation’s subsequent emissions and believe more research is needed on this industry’s rapidly growing demands on our country’s energy systems, along with its effects on our environment.”

In an interview with Marijuana Moment at the time, pro-legalization Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA) said that “there are some important nuances” when it comes to cannabis policy and the environment.

He said that, even amid extreme drought conditions in California, there are water sources that should be providing resources to the community and industry that are instead being diverted by illicit growers.

“We have not done a very good job of lifting up the legal market so that we can eliminate the black market—and that black market has really unacceptable environmental impacts,” he said at the time.

California itself has taken some specific steps to ameliorate the issue. For example, officials announced in 2021 that they were soliciting concept proposals for a marijuana tax-funded program aimed at helping small cannabis cultivators with environmental clean-up and restoration efforts.

The following year, California awarded $1.7 in grant money to sustainable cannabis growers, part of a planned $6 million in total funding.

And in New York, set rules meant to promote environmental awareness, for example by requiring businesses to submit an environmental sustainability program and explore the possibility of reusing cannabis packaging. Lawmakers there also explored promoting industry recycling programs and cannabis packaging made from hemp rather than synthetic plastics, though neither proposal was enacted.

Photo courtesy of Chris Wallis // Side Pocket Images.

The post Shift To Outdoor Marijuana Cultivation Could Cut Industry Emissions By Up To 76%, Study Finds appeared first on Marijuana Moment.